The south-western part of Ancient Nea Paphos was a privileged area due to its proximity to the port.

Therefore, it is not surprising that this location has housed several famous elite residences,

which played a significant role in the city's landscape.

The House of Orpheus, investigated by the project, is one of them.

Its location has been known since 1942 when a mosaic depicting Heracles with a lion was discovered accidentally.

Further excavations in 1963, revealed another mosaic panel displaying an Amazon standing by a horse.

Subsequent reinvestigation in 1978 concluded that both panels belonged to the same floor.

The site, called at this time the House of Heracles, was protected and awaited excavation.

Systematic exploration began in 1982 under the direction of Demetrios Michaelides on behalf

of the Department of Antiquities in Cyprus. Two years later, a magnificent mosaic depicting

Orpheus with the Beasts was unearthed, which led to the change of the previous name

to the House of Orpheus – the term denoting the entire complex of subsequent buildings

or the entire area of excavations.

The project continued intermittently until 2013, still under the direction of DM,

but since 2009 on behalf of the University of Cyprus) [Excavation reports].

Over the course of several years of methodical work, an approximately 1200-square-meter residential complex was uncovered.

Despite the incomplete exploration of the southernmost part, the architecture and richness of finds indicate

that the recovered buildings constituted the private residence of a wealthy individual.

In 2018, a new research project was launched, led by M. Rekowska and involving co-investigators and collaborators from Cyprus, Italy, and Poland

[Team].

This project aimed to further study and comprehend the significance of the House of Orpheus.

The central focus was to assemble and evaluate the architectural relics (remains of walls and stone decorations)

in order to identify functionality of various spaces within this urban house.

Through the collected data, we also aimed to establish the chronology of the House, shedding light

on its historical development over time. Additionally, the data analysis allowed for a better understanding

of the relationship between the layout of the House and the specific functions of each room, with a special

emphasis on the examining of their decorative elements.

The ultimate goal of this investigation was to address the question of the owner's social position

and material wealth, to the extent that can be provided by architectural data. By delving into the architectural

and decorative features, we aimed to gain a deeper understanding of the social status and material

affluence of the individual who resided in the House of Orpheus.

A comprehensive spatial documentation of the House of Orpheus was a vital component of the entire project.

In April 2019, non-invasive fieldwork was undertaken to record all architectural remains. The first task was to update

the plan of the house, while the second involved registering and cataloguing all decorated architectural elements.

All of this was undertaken to achieve the main goal: an in-depth examination of the interplay between

the layout, architecture, and decoration of the house.

Central to the documentation process was metric surveying, providing a two- and three-dimensional dataset

that mathematically describes the spatial layout of the site. Documentation methods like remote sensing,

laser scanning and photogrammetry were employed to ensure precise and reliable metric measurements,

each providing a distinct type of data. These methods not only served as illustrative techniques,

providing a new or improved depiction of the site, but also functioned as analytical tools, facilitating

the exploration of space and spatial relationships.

Considering the site’s nature (residential architecture with numerous stone elements), dimensions and volume,

and aiming for high quality and anticipated detail, 62 terrestrial laser scans

were conducted at 28M points resolution. Simultaneously, photogrammetric measurements were performed

to ensure consistent data. The majority of photogrammetry images were captured through extensive

aerial UAV survey, while others were obtained using classic close-range terrestrial methods.

Photogrammetry images underwent colour correction, orientation, referencing and processing to create

a raw photogrammetry surface model consisting of 150M vertices. The 450M point cloud model and the 150M vertex model

were combined to generate the final 3D surface model (more on documentation processing –

Documenting the House of Orpheus by M. Gładki.).

The acquired data was also utilized to generate an updated site plan, available in the form of

orthophotography and a drawn ground plan [ 2D documentation].

To trace historical structures and their decoration from a diachronic perspective, all decorated stone elements

excavated at the House of Orpheus were documented both descriptively and visually.

Several dozen of these elements still on-site were scanned and photographed, while those stored off-site were

photographed; several selected elements have been drawn [Image Repository].

Additionally, creating three-dimensional models of the most representative architectural elements

from different historical phases permits a more detailed study of these structures

[3D documentation].

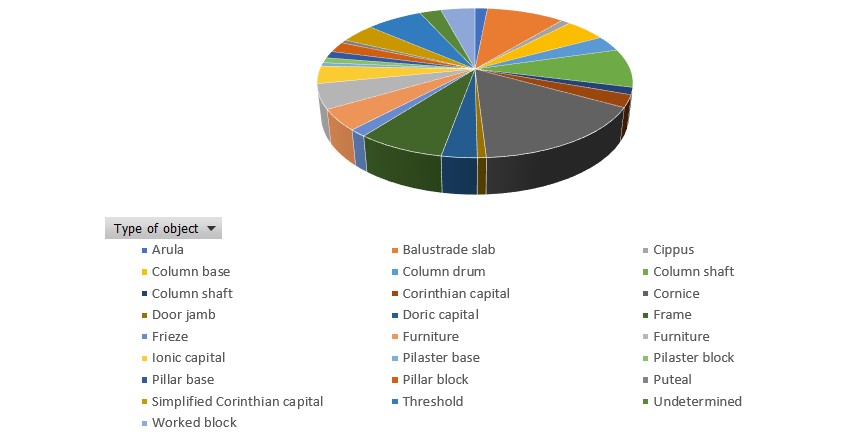

The registered objects attributable to colonnades, façades, doors, and the furnishing of open

and closed spaces across the buildings were identified, categorized, and catalogued.

The gathered information was used to establish a database of 263 items [Database].

Spatial data allowed the creation of a visualized version of the database based on orthoimage georeferenced

within the local system [ADHO Application].

We successfully integrated previously dispersed elements to recreate the decorations

of specific rooms (two peristyle courtyards, two entrances to reception rooms).

Finally, the diachronic analysis of architectural structures, supported by comparative research

and archaeological deduction, led to partial reconstructions of the House

whenever the evidence was sufficiently reliable. [Reconstructions].

The site has experienced multiple phases and has undergone various stages of development and use over time.

This conclusion is substantiated by the presence of artifacts from different time periods, including pottery,

coins, terracottas, lamps, and many others [Publications].

Subsequent owners adapted the houses to accommodate the needs of their families, therefore the site's architecture

also offers insights into its multi-phase nature. Various features such as wall traces, signs of rearrangement,

restructuring, blocked passageways, new room connections, and later additions indicate that the buildings

have undergone several significant changes and modifications throughout their history.

A comprehensive approach, based on a combination of digital documentation, photographs taken during excavations

and field observations, enables us to propose a chronological sequence of architectural changes throughout the site.

Clearly, the spatial organization within the house endured for more than one generation, in contrast

to the decoration of floors and walls, which aligned with the preferences of the residents and was more susceptible

to changing fashion. In contrast, the architectural decoration, being closely linked to the stone architecture,

exhibited greater durability.

For this reason, the study constructs a chronological framework divided into four main phases (Phases I-IV).

Three of these phases are associated with the development of the entire residence(s), while the fourth phase marks

a decline in the site's use, with a partial transition from residential to a workshop function. The proposed phases

are correlated with various factors that have influenced the site's development. These factors include earthquakes

that affected the region at different times (15 BC, 76/77 AD, the middle of the 2nd century, and multiple

occurrences in the 4th century AD), as well as other random events like changes in ownership and re-arrangements of space.

This analysis involves examining the decorated elements to identify specific periods or styles associated with each phase.

1. The buildings in question are believed to be part of the development plan of the entire city

of the Hellenistic period (4th/3rd century BC), and their layout provides insights into the early urban planning

phase of Nea Paphos. The area under study was likely divided into four units (U I-IV),

with a street separating the central plots U II and U III. The current appearance of U II suggests

that these plots might have originally housed peristyle houses, featuring a central columned courtyard

surrounded by rooms or spaces of similar sizes on three sides (W, N, E), with an entrance in the southeast

corner of the house. The existence of this phase is supported by various pieces of evidence: remains of

visible masonry in several excavated areas, a few small fragments of architectural details, and findings

from layers deposited just above the bedrock. In absolute chronology, this phase concludes

at the end of the 1st century BC.

2. Phase 2 is connected to the new arrangement of Unit II and the expansion of its area to encompass the former

street between the two central units (U II and U III). It might be linked to a reconstruction effort undertaken

at the very beginning of the Roman period, possibly following an earthquake in 15 BC. It cannot be ruled out

that during this phase, Unit I and Unit II were merged into a single property. This merging might have been part

of a broader redevelopment scheme for the insula(e). Modest bath facilities were established in the former Unit I,

in its northeast corner. This addition could indicate the adoption of Roman forms from other regions of the empire,

potentially reflecting cultural influences brought in by a new owner. However, the stylistic analysis

of the architectural decoration indicates that changes in the arrangement of the insula(e) occurred in at least

two stages, designated as 2A and 2B, concluding around the middle of the 2nd century AD. These two stages

are distinct from each other in terms of their stylistic features. In absolute terms, they can be respectively

placed in the first decades of Roman rule and between the Flavian and Trajanic periods.

3. The most significant development of the entire property occurred during a period spanning from the second half

of the 2nd century to the first half of the 3rd century (Phase 3). This phase is characterized by substantial

changes and advancements in the architecture and decoration of the site. Based on the construction of walls,

similar painting techniques, and architectural decoration, it is concluded that the buildings within the site

were merged into a single residence. This integration led to the creation of a property with distinct public

and private areas.

The presence of similarly dated decorated blocks indicates the homogeneity of the residence's decorative program

during this phase, which suggests a coordinated and deliberate effort in the re-design of the House.

At the same time, the decoration had not only aesthetic value but also played a functional role in hierarchizing

spaces and distinguishing between private and public rooms within the residence. It is precisely during

this period that the House of Orpheus can be seen as a means of self-presentation for the owner, who aimed to showcase

their status and identity through it. A mosaic inscription with the new owner's name - Pinnios Restitutos - in one

of the rooms reinforces this idea of personalizing the living space.

The former U I underwent a complete redesign to serve a public function. This transformation involved

converting it into the owner's showpiece, a prestigious space used for hosting guests, business partners, clients,

and friends. The western part of this north wing was occupied by representative rooms specifically used

for hosting feasts. These rooms are remarkable for being the only ones with preserved mosaics,

highlighting their importance in the social and ceremonial aspects of the residence. In the eastern part

of the north wing, baths were rebuilt, organized in a circular circulation with two heated rooms.

These baths served both the public area (former U I) and the private part (former U II), indicating a shared

and interconnected facility within the residence. The location and layout of the baths suggest that they were

occasionally made available to outsiders, implying that they could be used by visitors and not solely restricted

to the private use of the residents. The southernmost unit, the former U IV, was also entirely redesigned

to function as a self-presentation area. A new courtyard with a colonnade constructed in the Ionic order

and possibly an additional ceremonial hall with a monumental tripartite entrance in the Corinthian order,

showcased the owner's taste through architectural design.

4. The last phase (Phase IV) is characterized by a gradual change in the function of the living spaces,

transitioning from residential use to workshop rooms. These changes likely began in the middle of the 3rd century

and persisted until the site was entirely abandoned (possibly in the 5th century?). The transformation indicates a shift

in the purpose and activities conducted within the site. As part of the conversion process,

the circulation pattern changed, some entrances were intentionally blocked up, new openings in the walls

were created, and several rooms received new cement floors to accommodate the practical needs of the workshops.

A few elements of the original architectural decoration were repurposed - instead of serving their initial decorative role,

they were reused in the construction of new structures that catered to the specific requirements of the workshop rooms.

The reconstructed residence of the Phase 3 represents the pinnacle of its development. Its layout likely underwent

careful planning and design to optimize both private and public areas. This division indicates a strategic approach

to organizing the space based on the owner's need for privacy and his engagement with outsiders. A well-thought-out

system for gradually making the space accessible to outsiders implies a controlled and selective manner

of engaging with visitors and guests, possibly reflecting the owner's status and social standing. In particular,

the presence of baths facilities and two rooms decorated with mosaics mark a 'path of prestige.'

These features likely formed a ceremonial route or important spaces used for impressive displays during social events

or interactions with guests. The architectural decoration dating to Phase 3 represents an assemblage that is both

the most documented in terms of quantity and the highest in artistic level. Complex décor, including furniture

and fittings, would have been indicative of the owner's taste and penchant for luxury.

Based on the detailed analysis of the residence's features, it becomes apparent that the owner of the house

was a person of considerable wealth and social importance.

The detailed results of the research have been disseminated through publications,

conference papers, and lectures [Outreach].